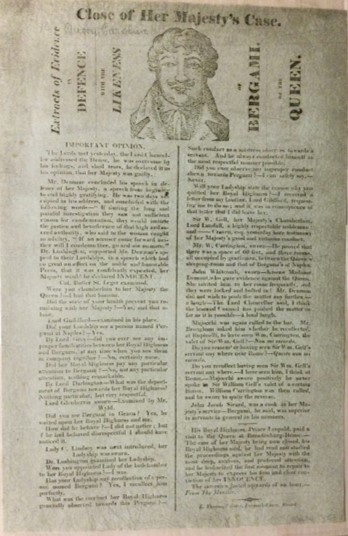

That evening a humiliated Caroline fell ill and took laudanum. The cause of her illness was probably a bowel obstruction or cancer but perhaps evidently there were rumours that she had been poisoned. Her exact cause of death was never to be determined as she refused to allow a post mortem.

Whatever the cause of her final illness, it was clear that she was dying and she put her affairs in order, making peace with one of the prosecution witnesses, her former ladies maid Louise Demont.

In her will she left her estate to William Austin and her jewels to Pergami’s daughter.

As to her remains, her wish was that her body be taken back to Brunswick in a coffin inscribed Caroline, Injured Queen of England.

She died on 7 August 1821.

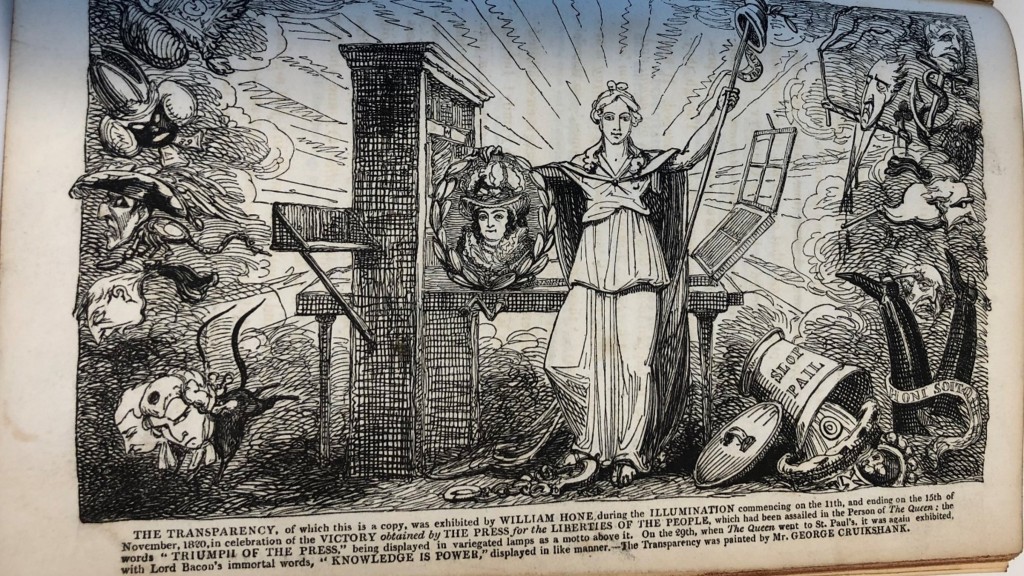

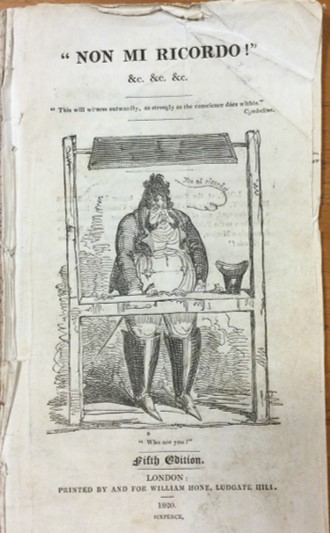

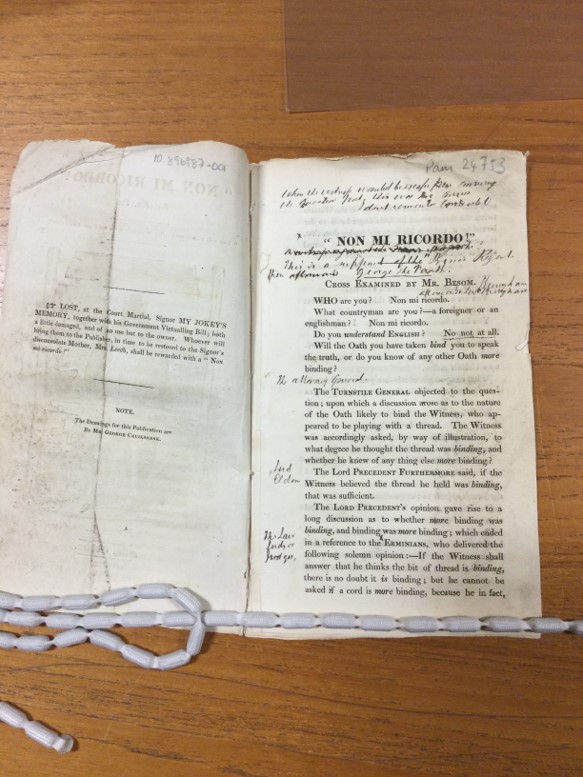

Hone did not feel bound to expressing condolences at the Queen’s passing. He laid Caroline’s death at the door of the authorities and rallied against their hypocrisy.

At the time of her death, George was in Ireland. In days following his couriers remarked that his mood was one of gaiety that they had not seen in years.

He ordered the minimum period of mourning – 3 weeks

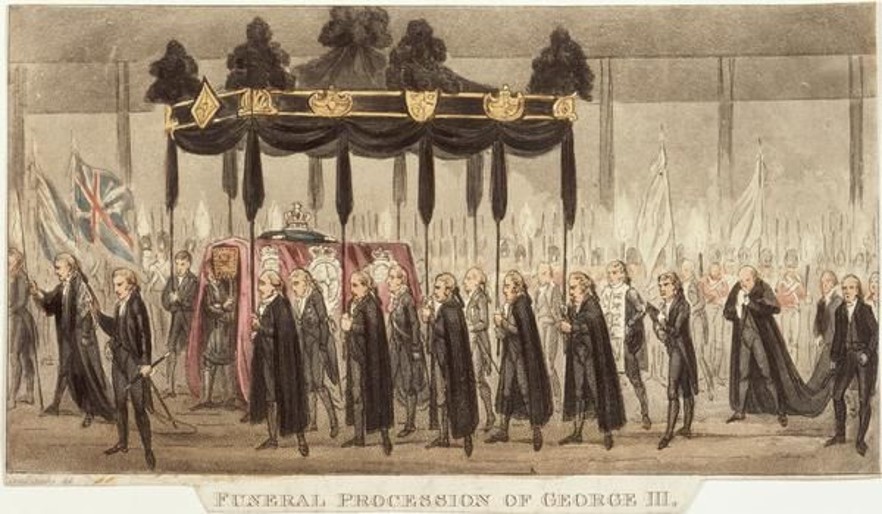

Caroline was not afforded a state funeral. The government’s main concern, as it had been for most of her life, was for Caroline to left Britain as quickly as possible

“An Irish wake, or the Whisky Club singing a requiem to the manes of the persecuted and – Queen”; George IV, William Curtis, Castlereagh, Bloomfield and others sit around a table with glasses of whisky in their hands. A satire on the death of the Queen and the dinner given in Dublin on 23 August.

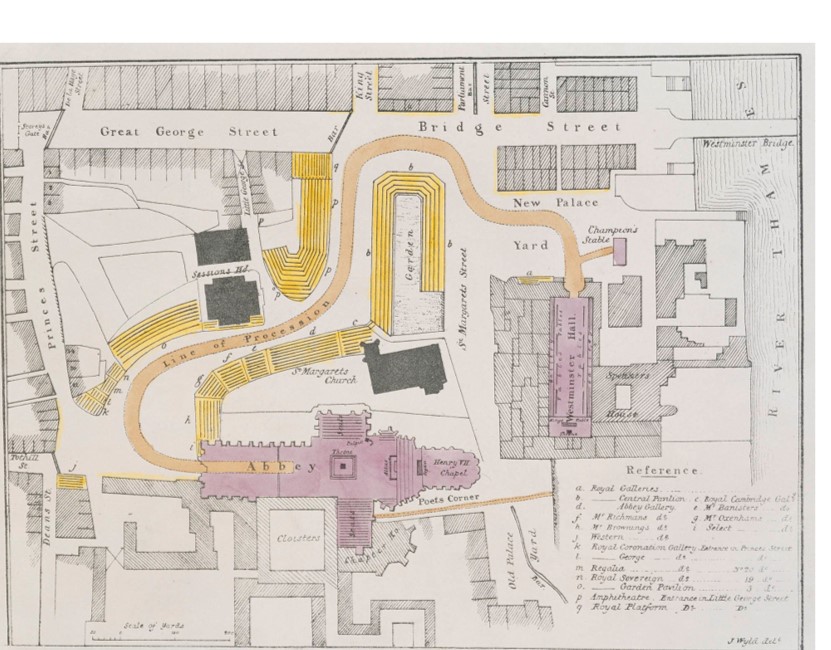

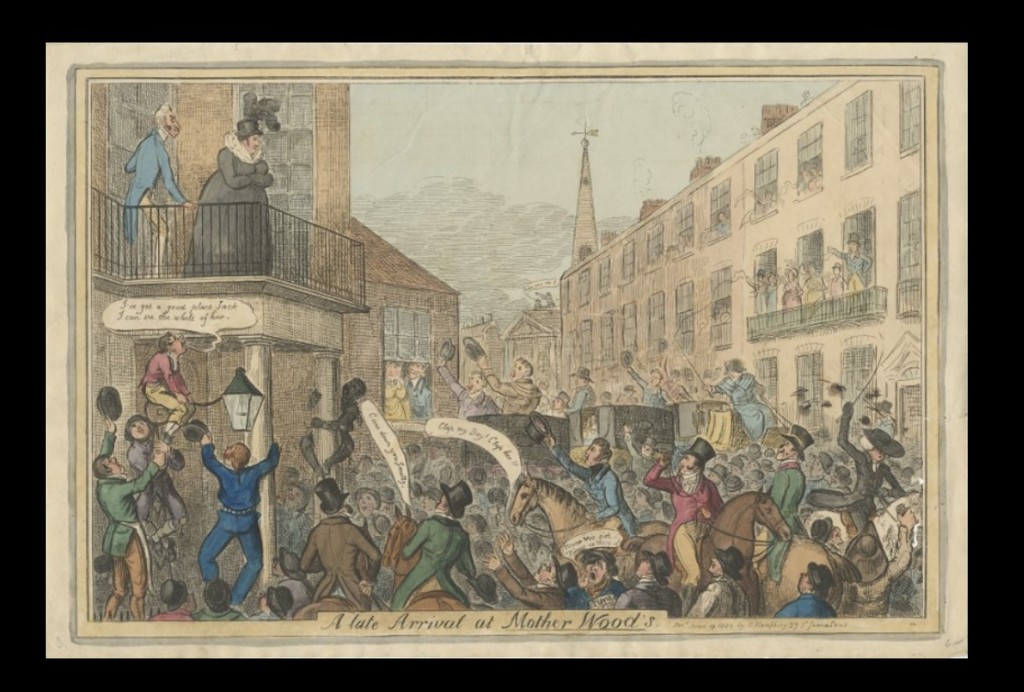

Queen’s funeral procession left Brandenberg House on 14 August 1821

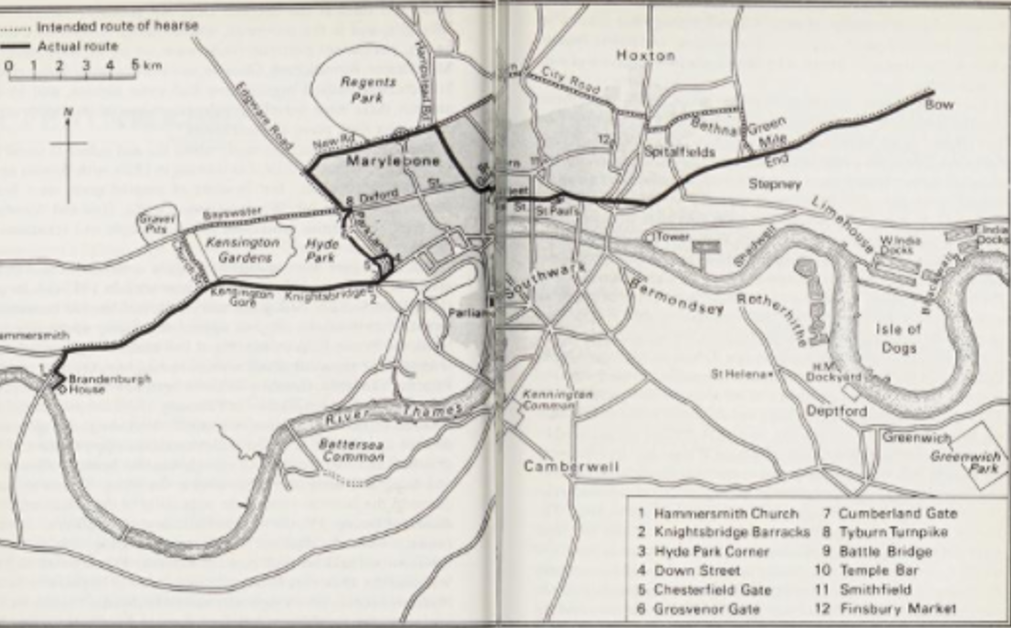

The progress from Brandenburg House to Hammersmith began before 6 am and was a dignified affair. Thousands of mourners, including many women, lined the route despite the torrential rain to pay their respects to a funeral procession headed by children from the Latimer’s Charity School strewing flowers.

The government proscribed route was to go skirt around the North of the City of London before heading through East London. Crowds who had been assembling in Hyde Park were determined disrupt these plans and reroute the procession through the city of London.

The first flashpoint was at 9.30 am at Kensington Church. To prevent the cortege from heading north to Bayswater, via Church Street, the crowd rendered the thoroughfare impassable by wagons, trenches and even burst water pipe. The procession was held, perhaps not entirely by coincidence, outside the home of William Cobbett, a leading radical and Caroline’s erstwhile press secretary.

A standoff remained until 11 am when the chief magistrate of Bow Street, Sir Robert Baker, arrived with a troop of Life Guards. Baker having surveyed the situation, gave orders for the procession to down Kingsbridge toward Hyde Park. The crowd had won round one.

Further standoffs took place at Hyde Park Gate and Hyde Park Corner where the mourners who following the cortege were swelled by the masses including members of trade associations who had been gathering in the Park since 6 am. On the orders of the Prime Minister, military reinforcements were called in and forced the procession northward.

As the top of Park Lane, crowds blocked the route and missiles were thrown in which a solider lost his eye. The solider was preventing from running his sword through a man by the chief magistrate. The procession was north of the city heading eastward.

It was at Cumberland Gate that the simmering violence erupted. The crowds had blocked the gate and the guardsmen forced it open and were clearing a path northwards. The crowds swarmed around the military’s horses, grabbing their reins and threw stones. The magistrate read the Riot Act and the military unleashed their swords and rifles.

The Peterloo massacre had taken place 2 years virtually to the day and memory of it must have been in everyone’s minds. When the crowds showered the soldiers with brickbats, stones and any missile to hand. The first shots were fired over the heads of the crowd but subsequently fired into the crowd. Bullets passed through some of the carriages in the cortege, their inhabitants were lucky to escape with the lives. Less fortunate was Richard Honey, a carpenter, who was shot dead. He had been a spectator. George Francis, a bricklayer, who had been a part of the crowd also died. Several others were severely injured.

The soldiers only stopped fire when an army officer, turned MP Sir Robert Wilson, intervened. In the ceasefire, negotiations took place with City officials and a route through the City was agreed. The procession passed through Temple Bar Gate and continued through without out further event through to the City and the East End towards Colchester.

The behaviour of the military shocked the public and the jurors of the subsequent inquests. They recorded verdicts of “wilful murder against a life guardsman unknown” for the death of George Francis, and “Manslaughter against the officers and soldiers of the 1st Guards” for the death of Richard Honey. Despite these shocking verdicts, no individual was ever specifically named as having been responsible or prosecuted for the deaths. On the contrary, Sir Robert Wilson was dismissed from the army for remonstrating with Life Guards.

At 4 am the coffin was placed briefly in St Peter’s Church Colchester. In an unseemly tussle ensued in which . Caroline’s Dr Lushington and other executors affixed to the coffin a plaque only to have it removed by the King’s representative, Mr. Taylor, with a Latin inscription approved by the King. The reported loud and threatening language was finally brought to an end when the mayor brought in the local militia to disperse the opposing sides. The coffin left the church three hours later

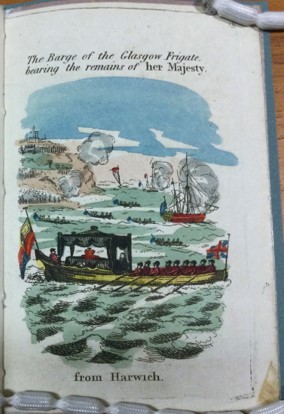

Caroline’s body left England from Harwich on 16 August 1821 on board on the Glasgow frigate.