Thanks to everybody who took part in Guildhall Library’s historical discussion groups in late March. In our lively discussions, we explored various facets of George III’s personality, his effectiveness as king, his relationship with his family, his descent into severe mental illness, his reputation at home and abroad and finally his depiction in literature.

Here is a precis of some of points that were made:

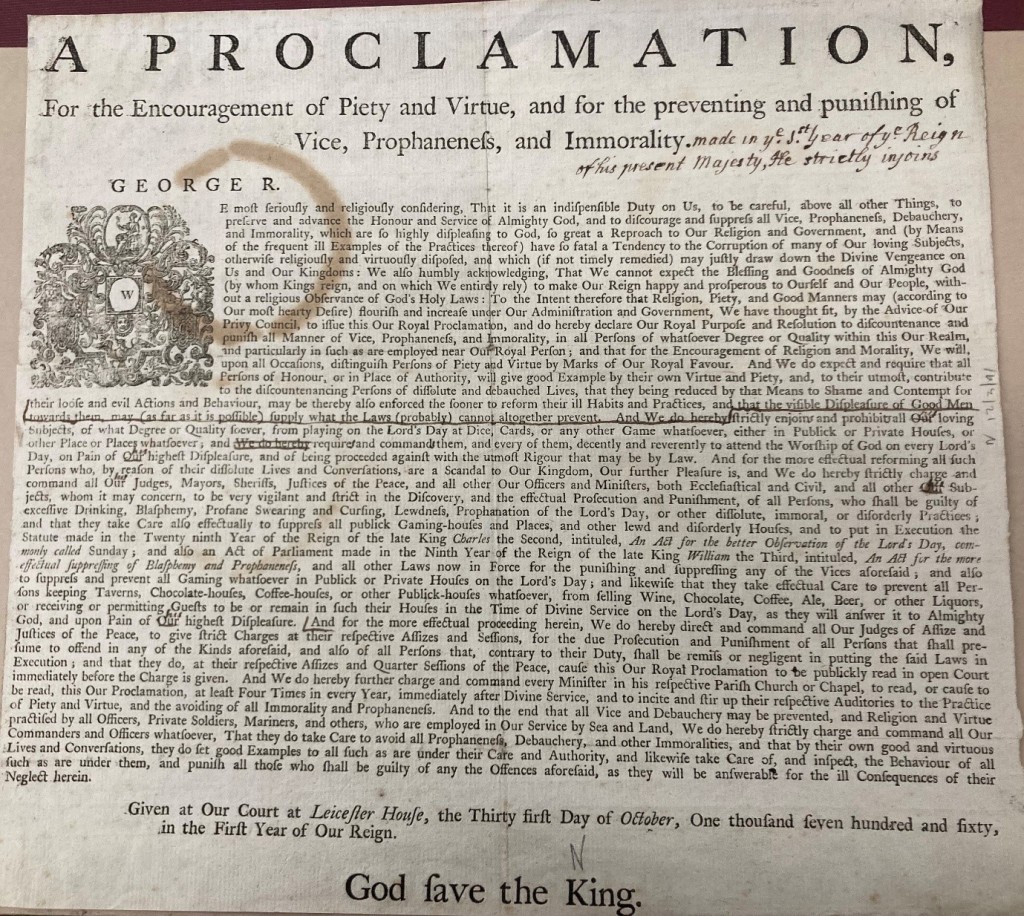

We started off exploring George III’s keen sense of moral responsibility and the fact that he discouraged vice and aimed to set an example of duty and respectability as king and through his family life which went down well with the middle class.

We then went on to reflect that the revolutionary settlement left George III in an ambiguous position as king. For while he could not be Catholic or marry a catholic or use the suspending power nor dismiss judges or maintain an army during peacetime, it wasn’t that clear what he could do as king apart from choosing and dismissing ministers. In fact, George was criticised for choosing Lord Bute as minister even though that was his prerogative and was neither unconstitutional nor unusual.

‘I have no wish but for the prosperity of my dominions… therefore must look on all who will not heartily assist me as bad men as well as ungrateful subjects…’ (Correspondence, ed. Fortescue, 6.151, no. 3973)

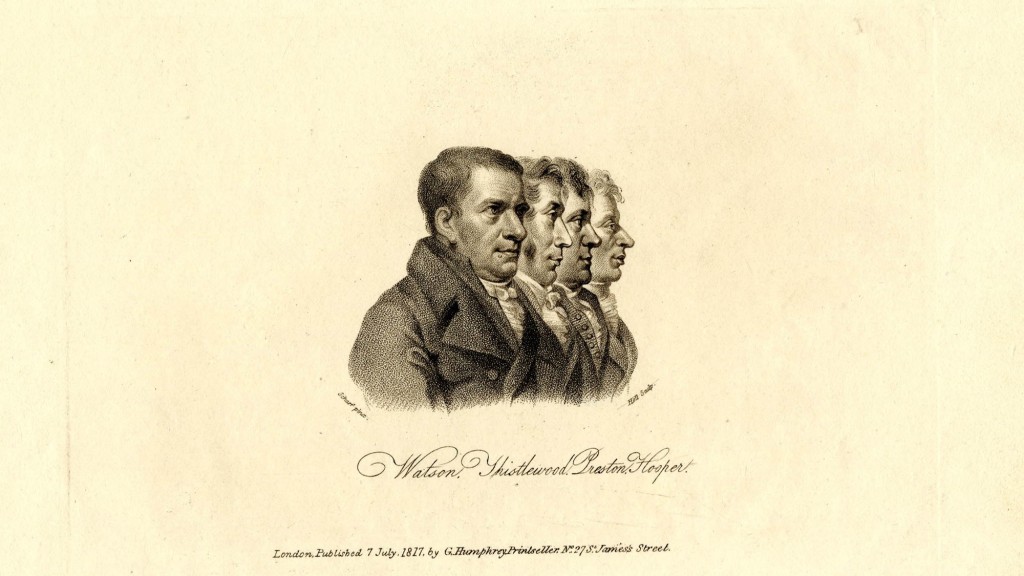

We thought about how George III took political opposition personally and how he often felt let down by his ministers and explored his difficulties in distinguishing between political and personal friendships and his frequently feelings of being betrayed. We reflected that this might have had to do with the fact that the idea of proprietary opposition, a key element parliamentary government was slow to catch on in the 18th century as the validity of opposition was tainted by ideas of treason.

We also spoke at length about how George found the routine of court life rather difficult and that his famously repeated interjections What? What? were attempts to fill awkward silences. We speculated that some of his social difficulties may have originated in his attempt to overcome his shyness with ambiguous assertions which others sometimes mistook for promises. And that his conservative attitude and need for a routine made him prefer ministers he knew and was comfortable with.

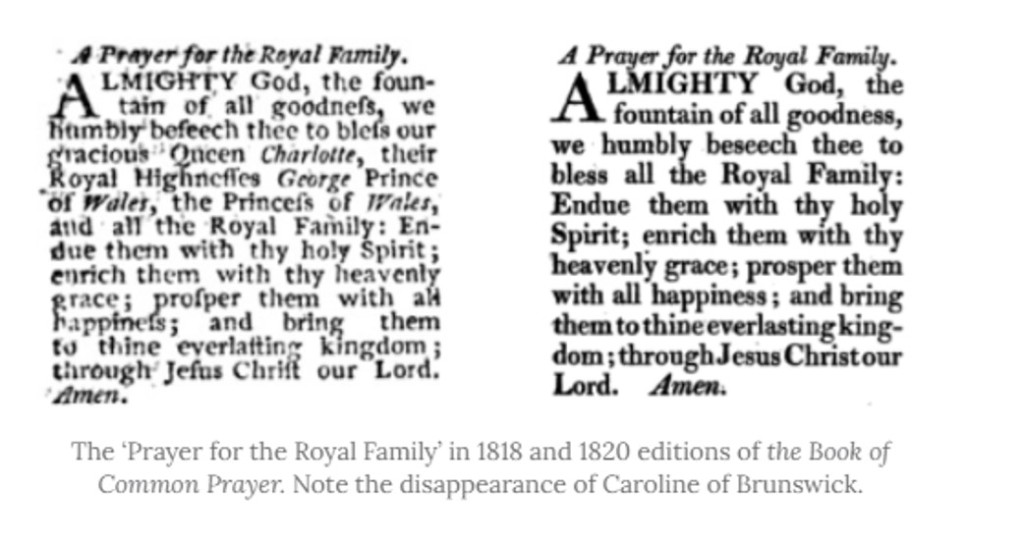

We considered that many of George’s challenges consisted in the fact that he was king in a period of decline for the crown which due in part to the great growth in public opinion fuelled by the expansion of newspapers and the rise in power of the first minister.

‘I do not pretend to any superior abilities but will give place to no one in meaning to preserve the freedom, happiness and glory of my dominions and all their inhabitants, and to fulfill the duty to my God and my neighbour in the most extended sense’ (Brooke, George III, new edn, 1985, frontispiece).

We reflected that while George had a reputation for being slow to read in childhood, this perceived deficiency in intellect was not evident in later life and that he kept meticulous records and amassed a vast library on multiple disciplines ranging from farming to astronomy and science.

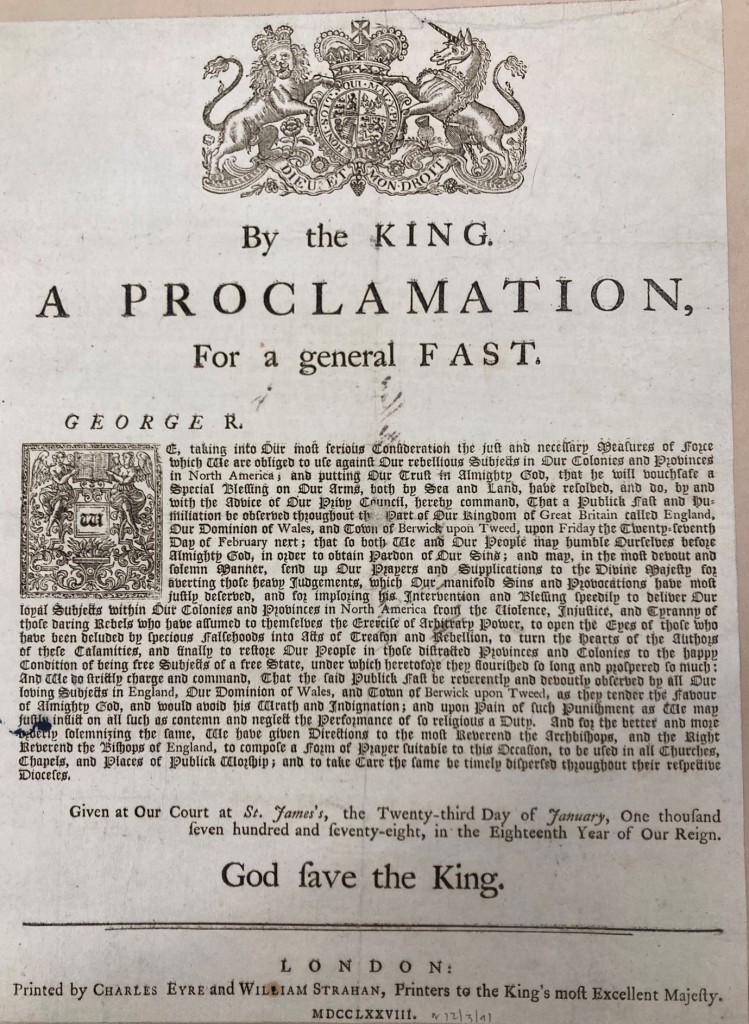

We surmised that George was unjustly claimed to be a despot in America when it was parliament who enforced taxes in America. Therefore, the Americans’ quarrel was with parliament rather than the king though they successfully personalized their struggle by blaming the king.

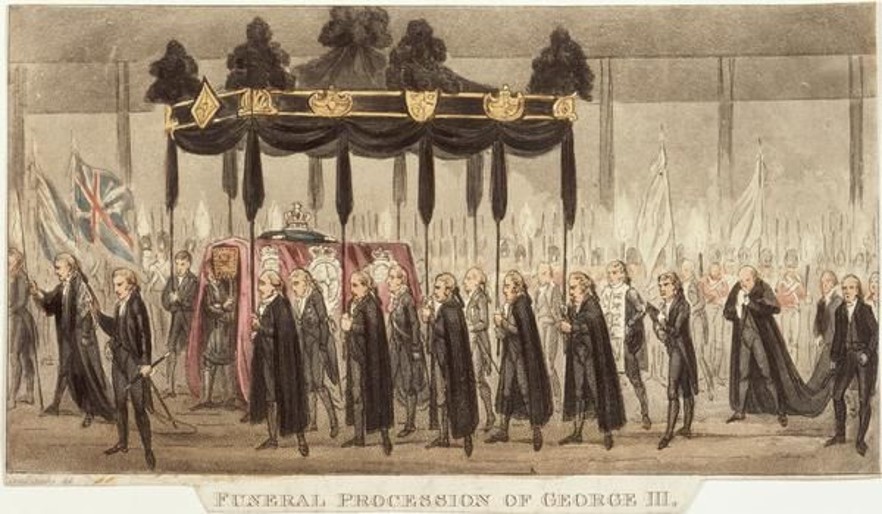

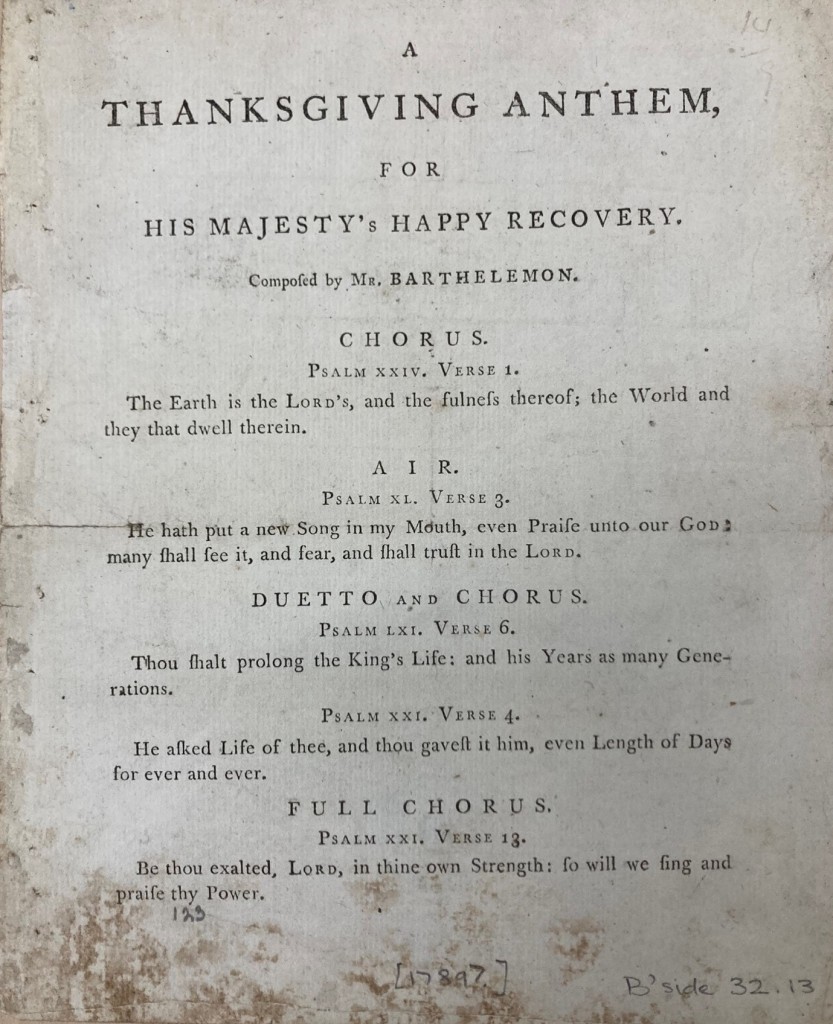

We examined his devotion to his wife and extended family. Both groups highlighted that he was hard on his son, the future George IV, and we made links to how his fraught relationship with his son mirrored previous Georgian kings’ difficulties with their first-born sons. We also talked about his relationship with his daughter Amelia and how her early death precipitated his final descent into madness.

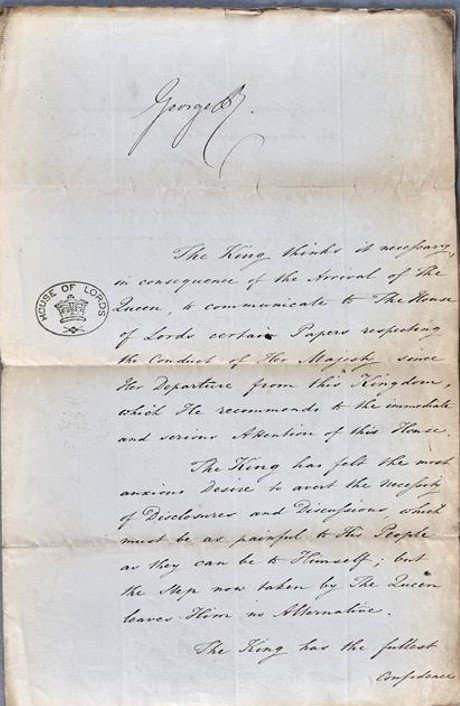

We talked about how some historians put his madness down to the genetic blood disorder called porphyria with symptoms of aches and pains, as well as blue urine. We agreed that it was more likely that George III did suffer from mental illness as indicated in the findings of a research project based at St George’s, University of London. We were able to see for ourselves, due to the digitisation of George III’s papers, that during his episodes of illness, his sentences were much longer. For example, a sentence containing 400 words and eight verbs was not unusual during episodes of his illness and he often repeated himself and used extravagant language and complex phrases. Features such as these are today seen in the writing and speech of patients experiencing the manic phase of psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar disorder. We also reflected that witnesses remarked upon the king’s incessant talkativeness and his habit of talking until he foamed at the mouth as well as described his convulsions.

We also thought about the portrayal of George III in literature and film. In William Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon 1844, the king was portrayed as cold and weak presiding over a hypocritical social elite. Robert Morley in the film Beau Brummell depicted him on the verge of insanity and then Alan Bennett’s play The Madness of King George which was later made into a film.

We concluded that, despite his illness, George III was a diligent king who won the sympathy and affection of his people. In our view it was more important for him to be a stable figurehead in prosperous and industrialised eighteenth century Britain than a ruler.

Sources

The correspondence of King George the Third from 1760 to December 1783, ed. J. Fortescue, 6 vols. (1927–8)

J. Brooke, King George III (1972)

Isabelle Chevallot Assistant Librarian