Introduction

Introduction

The idea for the ‘Great’ or ‘Monster’ Globe was conceived by MP, Charing Cross map maker, & Geographer to the Queen, James Wyld (1812–1887).

Wyld originally intended the Globe to be displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851, but problems around the lighting and size of the exhibit and Wyld’s desire to use it as an opportunity to promote his mapmaking business, ended in his having to develop his idea as a separate scheme. The concept had been in his mind for some time but the announcement of The Great Exhibition convinced him to bring his idea to fruition.

James Wyld entered Parliament in 1847. As the Liberal MP for Bodmin he “rapidly acquired a reputation for independence and outspokenness, particularly in the discussion on the Public Libraries Bill when he roundly accused the agricultural interests of opposing public libraries because they feared that libraries might divert the poor from drinking and so decrease the nation’s malt consumption” (Hyde, 119).

Wyld seems to have been a contentious figure whose activities often ended in disputes, the ‘Globe’ venture being no exception, with legal wrangles ensuing with architects, builders, residents and creditors.

The plan is put into action

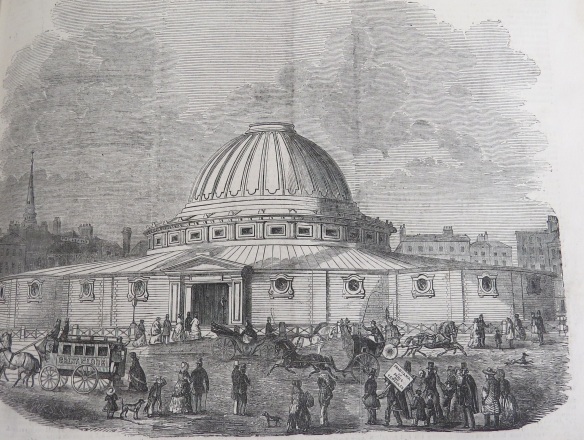

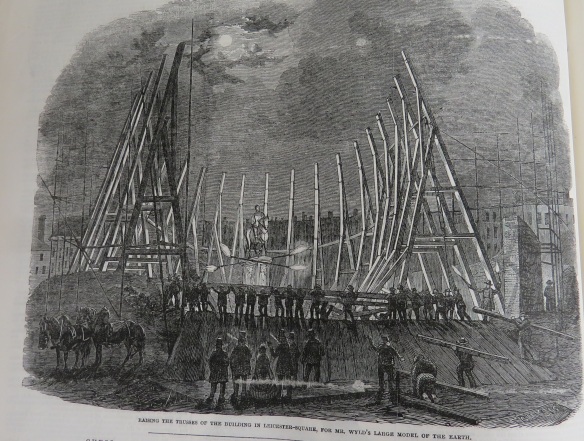

Wyld acquired a ten year lease on ‘garden’ land in Leicester Square for £3,000, (around £286,600.00 in 2014 values). In spite of local opposition, Wyld began to build the largest model of the Globe ever attempted. The original design was made by Edward Welch but this was later scaled down and substantially altered by H R Abraham. Welch’s design was thought unaffordable and perhaps unachievable.

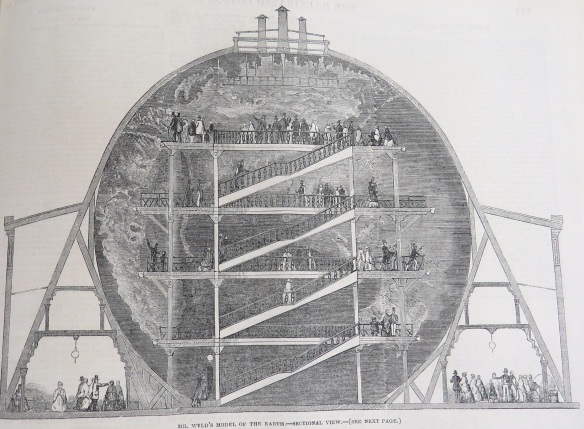

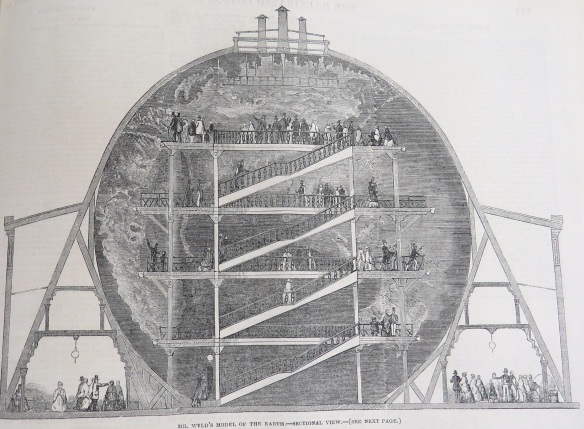

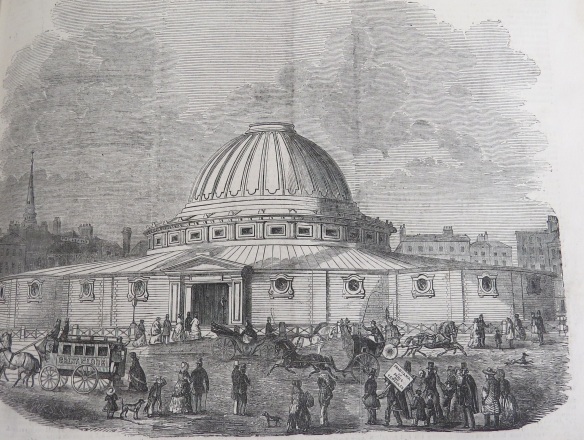

The building which housed the Globe was 90 feet across, and the Globe within was 60 feet 4 inches in diameter. It was built over a statue of George I which stood in the square and by the time the statue was dug up again, some ten years later, it had suffered a great deal of damage. The Globe was lit by daylight from the centre of the dome and by gas at night, the latter being problematic for the Hyde Park site.

When news of the intended project emerged, there was enthusiasm as well as some incredulity and amusement. Punch suggested that before building commenced, a party of huntsmen should be hired to exterminate all the cats living in the square, they also suggested that neighbouring housetops could be used for a display of the solar system and that visiting foreigners could be accommodated inside the Globe with lodgings corresponding to their relevant countries. In fact some of this was not so very far beyond Wyld’s own ambitions!

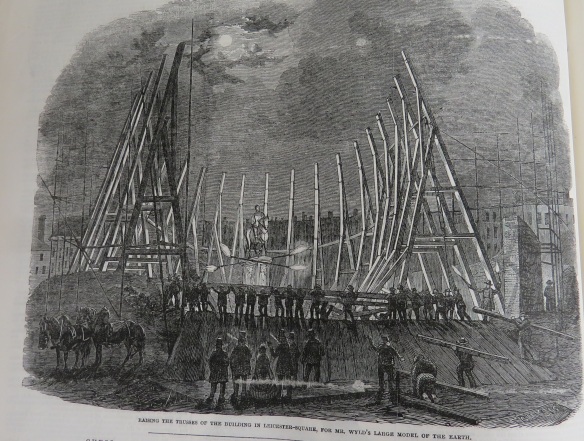

Construction of the Globe began in early March 1851. Hyde records an eyewitness (unnamed) reporting that “Amongst the great ribs of the growing structure a number of gas jets flared brilliantly, and made the struggling grass and shrubs greener than ever before. A few men were mysteriously moving amongst the ribs which looked like the skeleton of some enormous fish lying stranded” (Hyde, 120).

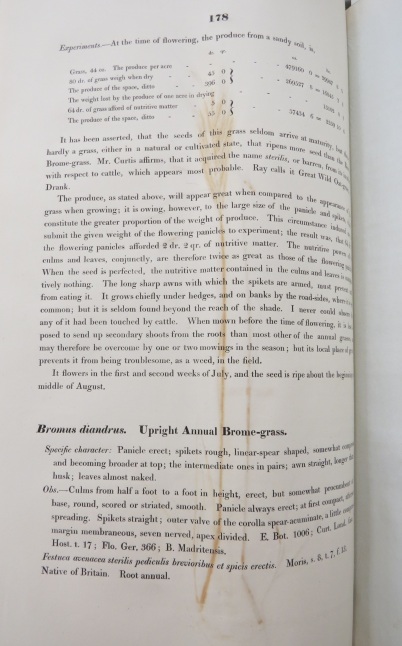

“Mr Wyld’s Large Model of the Earth.” Illustrated London News (22 March 1851): 234.

“Mr Wyld’s Large Model of the Earth.” Illustrated London News (22 March 1851): 234.

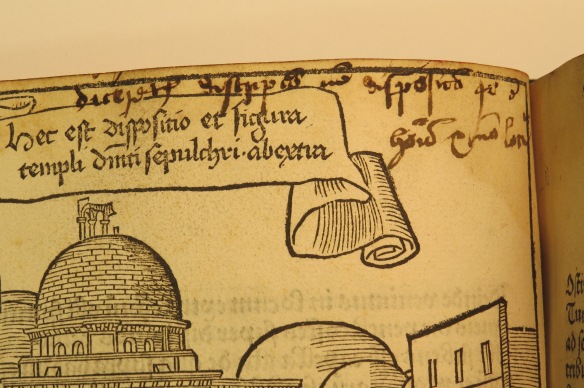

Plaster modelling on the inside of these ribs depicted the earth’s surface. This ‘concave’ view enabled the visitor to see all the physical features of the world when viewed from a series of staircases and platforms.

The visitor experience/public reception

The public flocked to the Monster Globe when it opened on 2nd June 1851. Hours of opening were 10am to 10pm on every day except Sunday and the entrance fee was one shilling. The large circular building had four entrances on the four sides of Leicester Square. Upon entering visitors found themselves in a circular passageway filled with Wyld’s maps, atlases, and celestial globes.

The convex side of the Globe was painted blue with silver stars and much of the interior design was by the theatrical scenery designer William Roxby Beverley. The interior was navigated by stairs and galleries; the world surrounding the amazed visitor who could see the oceans, the snow topped mountains and erupting red topped volcanoes (cotton wool was used to suggest the smoke).

Wyld’s giant ‘Model of the Earth’ was a great success and the attraction was so successful that in 1852 Wyld tried to get an Act of Parliament to authorize him to retain the building in Leicester Square but failed.

After the Great Exhibition

Wyld tried a series of strategies to increase visitor numbers, especially after the Great Exhibition closed. It was promoted as an educational experience and descriptive lectures were given throughout each day. In 1853 Wyld and the Globe were the subject of a scandal involving a display of fake gold in his Australian gold fields diorama, which may or may not have been ‘engineered’ to increase public interest in the attraction. Wyld created several new displays for the Globe including a model of the Crimea during the war (1853-1856) showing the position of the troops, day by day. It was his most successful exhibit and thousands visited to follow the War’s progress.

Wyld’s struggle to renew the lease on the land at Leicester Square finally failed and in 1861 the Monster Globe was taken down and sold for scrap. Legal wrangles followed the closure when Wyld failed to restore the gardens as promised.

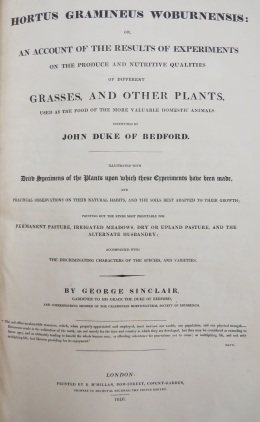

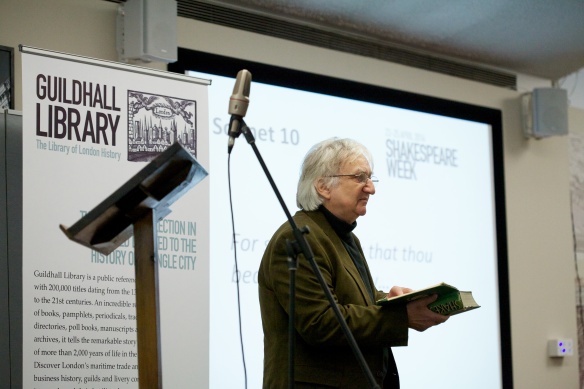

Reports, keepsakes and guides on the Great Globe at Guildhall Library

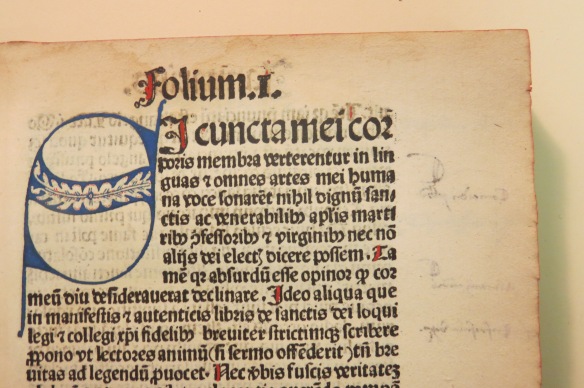

The Library holds guides, journal articles and keepsakes on the Great Globe including:

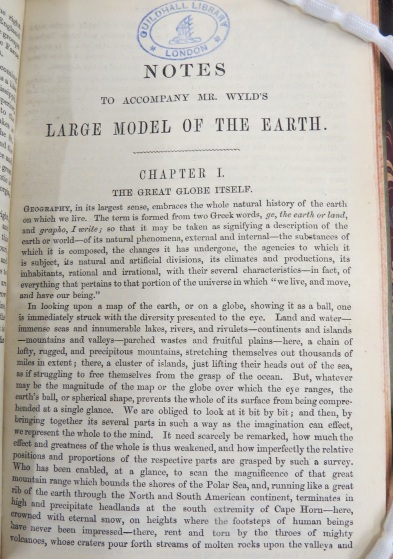

Notes to Accompany Mr Wyld’s Model of the Earth. Leicester Square. 1851 which was written by Wyld to promote the attraction (and his map business) and dedicated to HRH Prince Albert. The dedication celebrates past discoveries and the support for geographical research offered by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The ‘Notes’ are full of descriptions of countries, continents and oceans to accompany the exhibition as well as detail on the purpose and construction of the Great Globe itself.

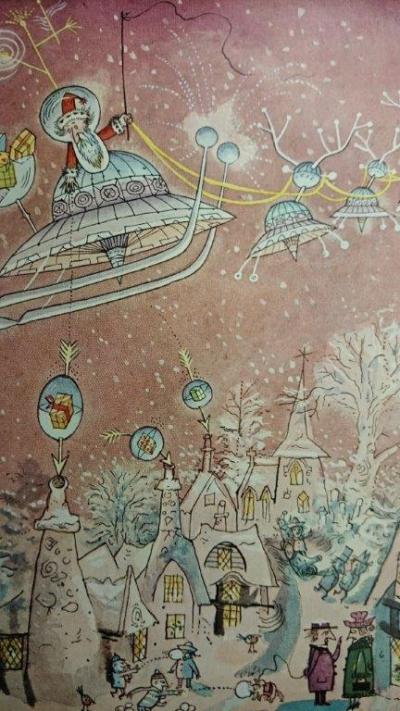

This charming illustration below is from The Little Folks Laughing Library “The Model of the Earth” 1851 by F W N Bayley.

This charming illustration below is from The Little Folks Laughing Library “The Model of the Earth” 1851 by F W N Bayley.

Having admired the alligator on his visit to Egypt, Jack exclaims:

“One enormous alligator

Kept me, I think, rather later;

For I thought he’d swallow me, bones and all,

And then I couldn’t have come at all!”

Frederick William Naylor Bayley (1808–1852) was the first editor of the Illustrated London News but also wrote verse for newspapers, popular song lyrics and fiction. He was nick-named ‘Alphabet’ and sometimes ‘Omnibus’ Bayley. The volume is written in verse and dedicated to James Wyld Esq. MP

“For we’re told that a man uncommonly WYLD

Has built up a Globe there for every child”

Find out more

There were reports on the Great Globe which you can search online or read in hard copy at Guildhall Library. Our collections include contemporary periodicals including The Illustrated London News and The Builder as well as numerous guides to London published to co-incide with the Great Exhibition e.g. The British Metropolis in 1851: a Classified Guide to London: so arranged as to Show, in Separate Chapters, Every Object in London Interesting to Special Tastes and Occupations. London : Arthur Hall, Virtue 1851.

Jeanie Smith

Assistant Librarian

References

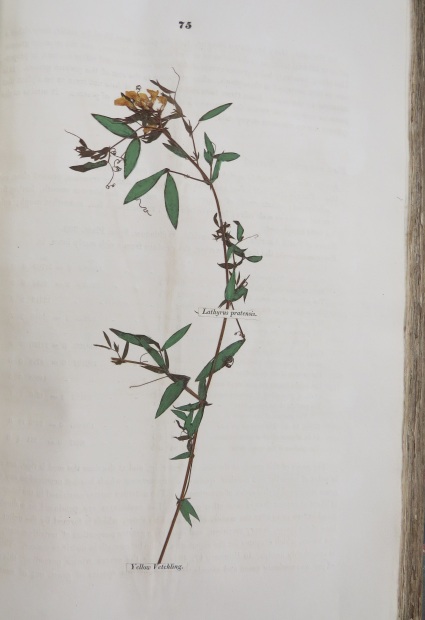

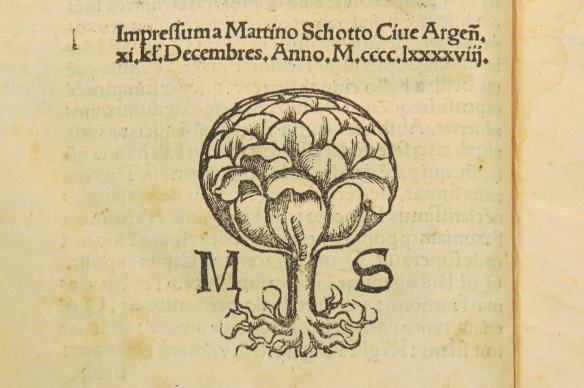

Bayley, F. W. N. (Frederic William Naylor) The Model of the Earth 2nd ed. London : Published for the author by Darton and Co, 1851.

Hyde, Ralph. “Mr Wyld’s Monster Globe.” History Today 20.2 (February 1970): 118-123.

“Mr Wyld’s Large Model of the Earth.” Illustrated London News (22 March 1851): 234.

“Mr Wyld’s Globe in Leicester Square” Illustrated London News (29 March 1851): 247-248.

“Mr Wyld’s Model of the Earth.” Illustrated London News (7 June 1851): 512.

Timbs, John. Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis; with nearly Sixty Years’ Personal Recollections. London : J. S. Virtue & Co, 1867.

[Wyld]. Notes to Accompany Mr Wyld’s Model of the Earth. Leicester Square. 1851.