Although the trial in Parliament had been paused. In the press, it was The Times took the lead in fuelling press outrage at the Queen’s treatment, running brazen attacks on a ‘debauched’ king. A popular petitioning campaign in her support eventually attracted over a million signatures

And Caroline’s supporters took to the streets. Large public meetings and processions in support of the Queen had begun to sweep the nation. The issue ‘took possession of every house or cottage in the kingdom’, recalled William Hazlitt. ‘Every man, woman and child took part in it …nothing was thought of but the fate of the Queen’s trial’.50,000 protesters carrying anti-government banners were parading on a weekly basis through central London. By October the numbers meeting at Piccadilly had reached 100,000. They came even by boat in their tens of thousands to Caroline’s secluded residence Bradenburgh House in Hammersmith with deputations. And in contrast to the events of Peterloo in 1819, the government stood by and did virtually nothing. Meetings organized in support of Caroline couldn’t easily be denounced as Seditious Meetings Act 1819.

The respectable middle classes and an unprecedented number of women attended meetings in support of Caroline. For a large number, if not a majority, they were drawn to the meetings for reformist or radical policies. Their support for Caroline was based in respect for the Constitution and loyalty to historic institutions. Their opposition to the Queen’s trial was because it an assault to the constitution and dangerous to the honour and dignity of the Crown. Meetings called for these purposes were always going to find a sympathetic magistrate would grant permission to hold the meeting.

The strategy didn’t go entirely to plan. There were a couple of damaging slip-ups, Lieutenant Flynn, a naval veteran of 16 years, fainted when he was caught out during cross-examination.Another lieutenant, Joseph Howham, one of Caroline’s foundlings from Montagu House perhaps gave one of the most unconvincing explanations as to why Caroline and Pergami shared a tent. Apparently it was because Caroline was afraid of pirated.Even Queen’s Counsel, Denman, who implied Caroline’s guilt when he suggested that Caroline should be allowed to go away and sin no more.

As ever, it was down to Brougham to make good any damage. He claimed that he had evidence of conspiracy which witnesses had be financially induced to give false witness and that he would call for an investigation – an investigation which would have led back to George

Queen’s “triumph”

On 6 November 1820, the House of Lords finally delivered its verdict on Queen Caroline’s alleged crime of adultery. It came as no surprise that she was found guilty, but the margin of victory was slender: a mere nine votes.

Within days the government of Lord Liverpool dropped its case, fearful that it would be defeated in the House of Commons, and perhaps mindful that the king could be impeached for his illegal first marriage. The country erupted into a frenzy of celebrations at ‘the death of the Bill’. Across the country, supporters organised, processions, marches, bell-ringings, fireworks, gun salutes. There were also occasional outbreaks of disorder.

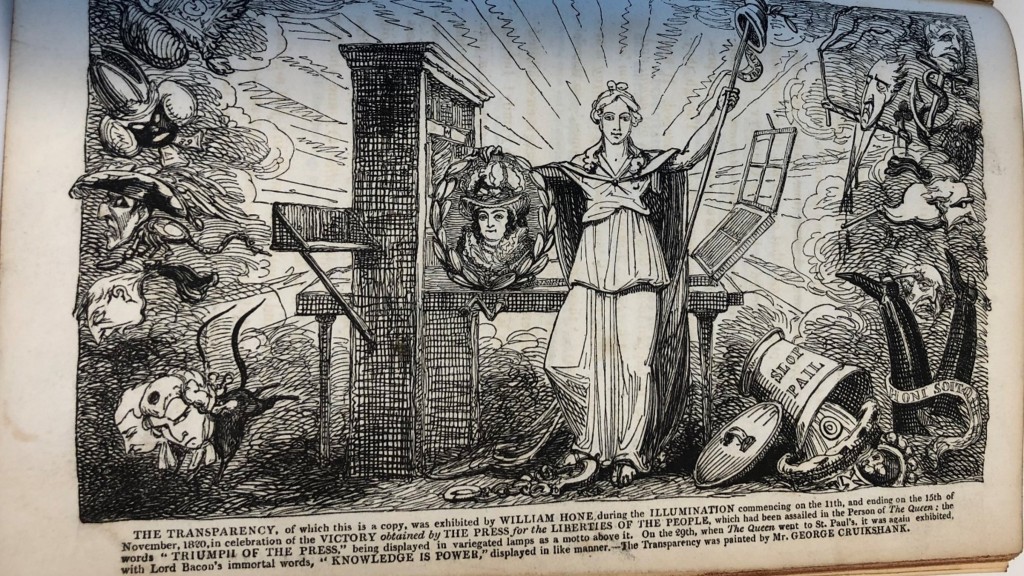

On 11 November, central London was illuminated. One of the ways to illuminate a dwelling was to mount a transparency of an image on a window and position a light source behind it to create a luminous effect. Press reports picked out William Hone’s “splendid illumination’ on display at his shop on Ludgate Hill for four days. According to the emphatic text beneath the image, the transparency was displayed for the whole four days ‘in celebration of the VICTORY obtained by the THE PRESS for the LIBERTIES OF THE PEOPLE, which had been assailed in the Person of The Queen’. Perhaps foreshadowing Caroline’s demise in popularity Hone gives equal force to Liberty and the sacred printing press but reduced Caroline to a trophy-like roundel portrait in a laurel wreath. In Hone’s understanding of the affair, Caroline is as much the product as the producer of ‘the liberties of the people’.

On 29 November Caroline attended a service of thanksgiving at St Paul’s cathedral. She was accompanied by 500 horsemen and a crowd of 50,000 people. It was intentionally provocative and a carefully orchestrated imitation of a coronation. Although the service was a stage-managed, anti-government spectacle. The psalm ordered for the service was no. 140—’Deliver me, O Lord, from the evil man”. They were were careful not to break the law and include Caroline’s name in the litany

With the government on the back foot and republican uprisings in Europe, the mood seemed ripe to turn Caroline’s victory into political action. The Examiner reported of a meeting of the alderman of the City of London at which it was agreed to ask the king to dismiss the government. Alderman Robert Waithman insisted that without reform, ‘a revolution or the establishment of a military government must ensue’. To give itself some breathing space, the government prorogued Parliament until 23 January. Caroline was in a position to make demands a royal residence, an annuity and the re-inclusion of her name in the liturgy. The Government were keen to get Caroline out of the country and made her an offer of an annuity of £50,000. The sticking point was the liturgy. In public statements she announced that she was resolute on the issue.

However in late February Caroline probably made her biggest error. She accepted the £50,000 with the government not making a concession on the liturgy. She had given in to the government. Brougham was furious, she had sold out and ‘she had destroyed her image as the victim of oppression, at one with the people’ Caroline was disillusioned. She reportedly wrote, ‘No one in fact, care [sic] for me . . . and this business had been more cared for as a political affair, than as a cause of a poor forlorn woman’.